Mephedrone (4-MMC) is a popular substance in the cathinone class, but users who insufflate (snort) it often report significant nasal pain, irritation, and potential long-term damage. This discomfort is not caused entirely by the mephedrone molecule itself, but by impurities left over from a careless manufacturing process.

This guide explains the likely cause of this issue and outlines methods to potentially reduce the harm associated with insufflating impure mephedrone.

The Problem: Synthesis Byproducts

While grey market cathinones were often quite high purity, bans of 3-MMC and 4-MMC have lead to less sophisticated clandestine production, and while some grey market websites do conduct quality control, street sellers almost never do. Therefore, produced cathinones can vary widely in purity. A common issue is the presence of leftover reactants, primarily unreacted methylamine and hydrochloric acid (HCl*).

Methylamine is a major cause of the distinctive smell of mephedrone, often described as smelling like “cat urine”. Not only is the smell unpleasant, but methylamine and hydrochloric acid attract water, preventing excess hydrochloric acid from evaporating because the molecules don’t want to be separated from water.

Quickly Test for Excess Acidity

When these impurities are present the crystals often damp and almost oily feeling, with a strong odour. If you have litmus paper, this is obviously the fastest way to test pH. A simple qualitative test can help confirm if your sample has a high acidity with normal baking soda.

- Create a concentrated solution of 4-MMC in a small amount of water, about 200mg in 1mL of water is good

- Add a tiny pinch of bicarbonate of soda to the solution.

- Observe the reaction. If significant and sustained fizzing occurs (the release of carbon dioxide), it suggests the presence of excess acid.

- Evaporate the liquid in warm air to get back 4-MMC crystals

Purification Method 1: Simple Heating (Decarboxylation/Drying)

A simple heat-purification technique can help reduce these volatile impurities. This process aims to drive off trapped water, unreacted methylamine, and free hydrochloric acid.

Procedure:

- Finely grind your mephedrone powder to maximise surface area.

- Spread it in a thin, even layer on a heat-proof dish (e.g., a Pyrex or ceramic plate).

- Place the dish in an oven to between 100-120°C (212-248°F) for 2 to 10 hours. The substance should not melt or turn into a goo at this temperature.

- Allow it to cool completely before handling.

The result should be a product with a noticeably reduced smell and less corrosive properties.

Purification Method 2: Water Recrystallisation (Advanced)

For those with more chemistry knowledge, recrystallisation is a more effective method for separating mephedrone from water-soluble impurities like methylamine hydrochloride. This process exploits the difference in solubility of mephedrone in hot versus cold water.

Principle: Mephedrone is soluble in hot water but much less soluble in very cold water. Many impurities remain dissolved in the water even when it is cooled.

Simplified Procedure:

- Gently heat a minimal amount of distilled water (e.g., ~3mL per 1g of product) to around 80°C.

- Dissolve your mephedrone completely in the hot water.

- Cover the container and allow it to cool slowly to room temperature, then transfer it to a refrigerator or freezer to cool to around 1°C.

- As the solution cools, pure mephedrone crystals will precipitate out of the water. The impurities will largely remain behind in the liquid.

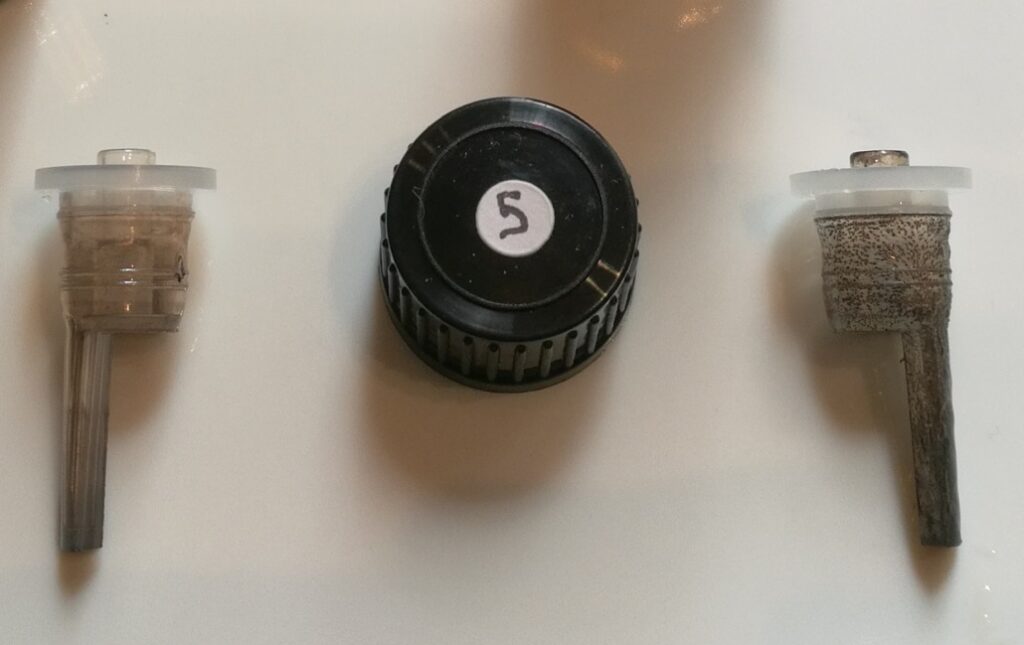

- Separate the crystals from the water and allow the crystals to dry thoroughly.

- You can also keep the water and dry it out which will give you all the impurities mixed with a little bit of 4-MMC.

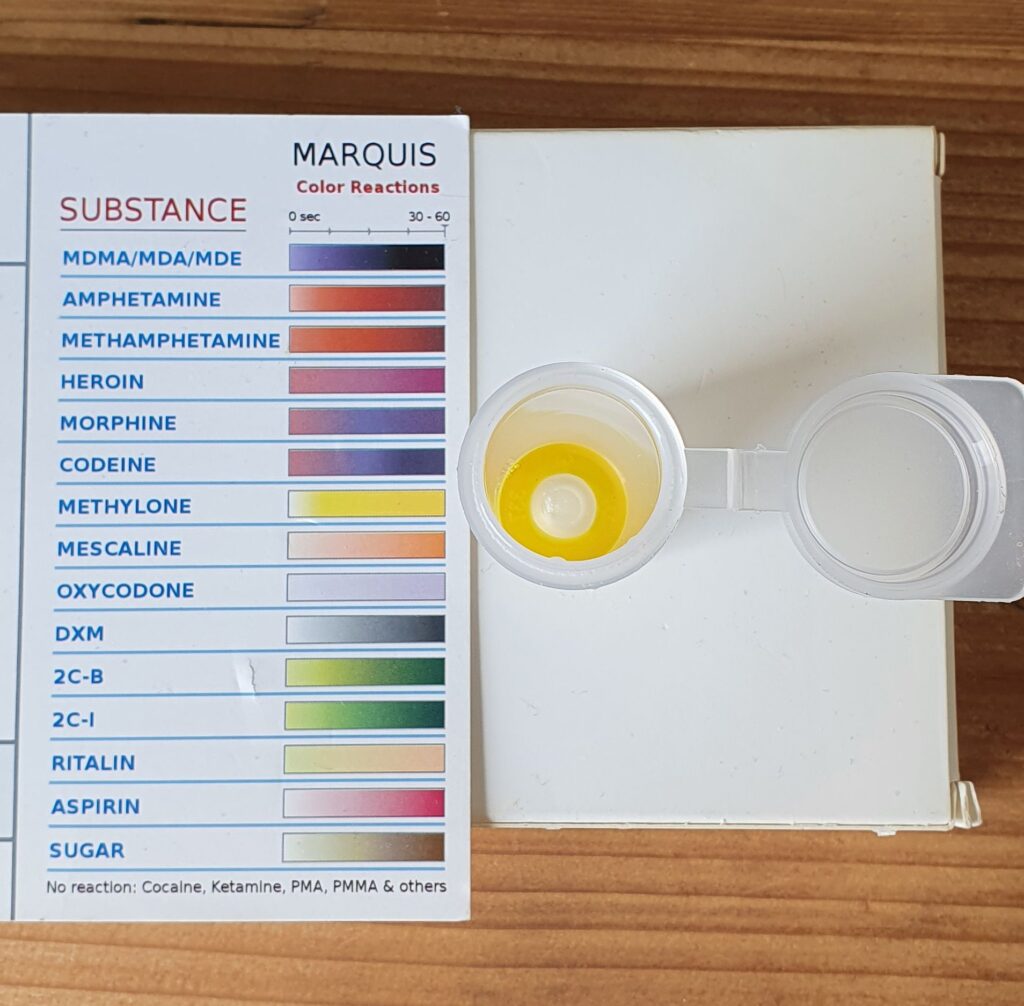

Crucial First Step: Reagent Testing

Before attempting any purification or considering consumption, it is essential to verify the identity of your substance. Reports suggest that a significant percentage of substances sold as mephedrone in Europe are, in fact, different and potentially more dangerous chemicals, such as 4-CMC.

Purification methods will not change an incorrect substance into the desired one. The only way to gain a better understanding of what your sample contains is to use a comprehensive reagent test kit. Always test your substances before you do anything else.

* n.b. HCl is spelled with lowercase L, not HCI as in Hotel Charlie India! It denotes hydrogen chloride, which is a gas at room temperature but LOVES dissolving in water so much that it is normally found in solution, which we call “hydrochloric acid” because the hydrogen ions separate apart from the chloride ions once dissolved.